Elisabeth Frink 1930-1993

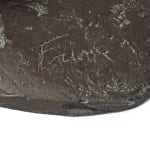

Incised with the artist’s signature, ‘Frink’ and numbered 2/6.

Further images

Provenance

With Alwin Gallery, London, February 1989, where acquired by the previous owner.Private Collection, U.K.

Literature

Sarah Kent and Bryan Robertson, Elisabeth Frink, Sculpture: Catalogue Raisonné, Harpvale Press, Salisbury, 1984, pp.168-9, cat.no.150 (ill.b&w, another cast)

Sarah Kent (ed.), Elisabeth Frink, Sculpture and Drawings 1952-1984, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1985, p.51, cat.no.45

Bryan Robertson, Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1950-90, The National Museum for Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C, 1990, p.41 (ill.b&w, another cast)

Annette Ratuszniak (ed.), Elisabeth Frink Catalogue Raisonné of Sculpture 1947-93, Lund Humphries in association with the Frink Estate and Beaux Arts, London, 2013, p.104, cat.no.FRC175 (ill.b&w, another cast)

Calvin Winner (ed.), Elisabeth Frink: Humans and Other Animals, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, 2018, p.107 (col.ill.)

Elisabeth Frink was 9 when war broke out. Her father was an officer in the 7th Dragoon Guards and the Indian Army cavalry regiment, Skinner's Horse, and away for most of the war until the family were reunited in 1945. The young Frink spent much of the war years at her grandparents’ home near a military airfield in Suffolk, where she heard bombers returning from their missions, saw dog fights and planes crashing into the surrounding fields; their twisted and broken wreckage a testament to man’s violent nature, but ultimately also, his innate vulnerability. Large Bird is from a period (the mid-1960s) when Frink’s work was what Laurie Lee, an art college friend, described as; “Jagged as shrapnel, these forms are both wounds and weapons; they bristle with terror or stretch in long cries of triumph. They are shades of our violent past, as well as the masks of our present selves.” Frink herself acknowledged that birds in her work are; “really vehicles for strong feelings of pain, tension, aggression and predatoriness.” Large Bird demands our attention to the form's sudden, predatory glance to the right in mid-stride; as if just detecting prey and looking for its origin.

In one respect this work is about sight which for a sculptor, is a challenging subject. In fact as Julian Spalding's states in her essay in Frink's Catalogue Raisonné; “Sculpting sight became one of Frink’s most absorbing and remarkable ambitions”. Moreover, in Frink's work evil is almost always blinkered, whether by goggles, the carapace of a helmet or as in Large Bird, the virtual absence of eyes. To choose to be blind to the consequences of one's actions in conflict was for her, the ultimate human transgression.

Large Bird is a fine example of Frink's mature sculptural style which is characterised by her rough manual treatment of surface. It's an approach that makes the work a wonderful record of the artist's creative process. At the same time, the heavily worked and textured surfaces help to project the vitality and dynamic movement of her subjects.