Adrian Heath British, 1920-1992

Heath was “one of the best artists in England with an intelligence, a set of values, and an accomplishment roughly comparable to Robert Motherwell’s”. (Bryan Robertson OBE. Critic and Director of the Whitechapel Gallery)

Adrian Heath was born on 23 June 1920 in Maymo, Burma. His father worked for the Bombay Burma Company managing teak forests. Heath described early life as “very much Somerset Maugham country”. At the age of 5 Adrian was sent back to England to live with his grandmother in a stately house just outside Southampton called Marchwood Park. In 1929 aged 9 Adrian was sent to board at a prep school called Port Regis in Dorset. His parents returned home on leave once every 3 years and he describes himself as a tough little boy with a vivid imagination which he used to torment his peers.

He recalled a talk given at his school by RH Wilenski, the leading voice on modern art before Herbert Read, with slides of work by Wyndham Lewis and Juan Gris. Later he focussed on a brass door handle and “it suddenly looked exactly like a section of a Juan Gris”, he realised “one’s vision could concentrate and one’s focus could change”.

After Port Regis he was accepted at Bryanston School in Dorset which had opened in 1928. Bryanston followed the American Dalton philosophy of education; with a liberal artistic focus upon the individual's development. Lucien Freud was another pupil. At Bryanston Heath read The Modern Movement in Art, by Wilenski, published in 1927. This book scathingly attacked the realism of Whistler, Sargent and Turner, all of whom the young Heath admired, but its teaching of the artist’s need to stay abreast of the times and to preserve his independence deeply influenced Heath in a way that can be traced throughout his artistic lifetime.

After a schoolboy stunt in which some bones from a cemetery vault were stolen, Heath appears to have taken the blame to shield a friend and whilst not expelled, left Bryanston in 1937. Following a year in a military preparatory school in Sussex, Heath, with his mind set upon becoming a portrait artist, persuaded his parents to allow him to go to Cornwall to study under ‘an estimable old RA’. That old RA was Stanhope Forbes, now in his 80s. Heath was the only full time student and was instructed in the correct observation of tonal values and other painterly skills. At the end of July 1939, on Forbes' advice, Heath applied to the Slade. At the outbreak of war he also applied to join the Somerset Light Infantry but being rejected, entered the Slade, by then evacuated to Oxford, in October. He remained for 2 terms joining the RAF in May 1940. Unhelpfully, the Slade at the time was very traditional; focussed on draftsmanship and the tenets of Renaissance painters.

Determined to do his bit in the expanding war effort, Heath redoubled his efforts to join the RAF. Heath suffered epileptic fits in his early life and conscious that his epilepsy would present a real danger to himself and many others as a pilot, he joined the RAF as a rear-gunner, rather than as a fighter pilot; a role his background would have more normally at the time, suggested. In the autumn of 1941 he was transferred to 101 Squadron Bomber Command. On his fifth sortie in a Wellington bomber, he was shot down on the Dutch coast, captured and ended up in the Bavarian prison camp Stalag 383. Here he met Terry Frost, 5 years his senior and a Commando with considerable active service who had been captured in Crete.

As a former art student, Heath received a few tubes of paint through the Red Cross, which he shared with Frost. They used sardine oil for their medium and brushes made from horse hair purloined from sympathetic guards. For canvas they employed hessian pillows and for size, barley from the camp’s soup. The friendship between Heath, nicknamed Toggle, and Frost endured until the former’s death. As Jane Rye comments in her biography on Heath; ‘Their temperaments were very different. Frost … famously ebullient and extroverted, with the ability to evoke in words the emotions of the time and place that had given rise to a particular painting. In Heath’s work, by contrast, one has the feeling that the excitement is not something that is being recaptured so much as discovered and experienced as the painting progresses”.

Frost described Heath as “the bravest man I have ever known”, a reflection undoubtedly suggested in part by his four 'beyond the wire' escape attempts, the last taking him close to the Swiss border resulting in a year’s solitary confinement. He had expected to be shot. In a Guardian interview a generation later he recalled reconstructing shapes in his mind from cracks in the walls of his desolate cell. The troublesome Heath was transferred to Stalag Luft before enduring the notorious retreat with his German captors in sub-zero, starving conditions to just south of Berlin where he was ultimately liberated by the Russian advance.

Following his ‘Operation Exodus’ repatriation, Heath got in touch with his old mentor, Stanhope Forbes, and spent a month painting in St Ives, also urging Terry Frost to move there. In the autumn he returned to the Slade adopting Victor Pasmore as his mentor. After Slade, Heath spent a year in France near Carcassonne with a fellow prisoner of war, Francis Andreiux. In February 1948 he held his inaugural exhibition at the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Carcassonne with 35 oil paintings in a largely bold post-Impressionist style; some showing an influence of Cezanne and suggesting the beginnings of a transition from realism to abstraction.

Heath was keen to divorce himself from realism and to be part of the contemporary art scene. He’d seen the influential Picasso and Matisse exhibition in London in 1946 but harboured a desire to anchor his departure from figurative depiction in rational principles rather than emotional whimsy. “I was anxious to get away from what I was looking at …” and to make the simplifications and distortions objective and not due to the whim of the artist in some emotional mood".

In Spring 1948 Heath returned to London to rejoin Terry Frost at Camberwell studying under Victor Pasmore. Heath developed the interesting duality of being both a Pasmore patron, collecting a number of significant works by the elder artist, and a devoted student. Heath’s work during this transitional period, edging towards abstraction, was strongly influenced by Juan Gris, Pasmore and at times, Seurat.

Writing about an experience, painting at Paddington Station, we can see the abstract artist struggling to emerge from his artistic chrysalis; “To begin with I had been creating the experience of space with a few marks on paper – later I had fallen back to imitating a particular environment.” He continued, “This realisation that the vitality of a drawing could lie in the relationship of the lines one to another rather than in their ability to communicate natural information, was a revelation to me".

Heath’s first wholly abstract painting was ‘Rotating Rectangles’, painted in 1948 and by his own account, the artist was wholly committed to abstract art by 1950; “I no longer worked from a visual experience but towards one”. In 1951 Heath was one of only six St Ives artists selected for the Artists International Associations Abstract Art show in association with the Festival of Britain, intended to celebrate the very best of contemporary British art. Alongside works from Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Wilhelmina Barnes-Graham, Roger Hilton and Terry Frost's seminal piece, 'Walk along the Quay', Heath exhibited 'Blue Abstract' and 'Blue Spiral'.

Heath was a central figure in the post-war role of British art, and in particular modernism and abstract art, as a building block, along with contemporary architecture, in the reconstruction of a better, modern world. He was instrumental in the concept, first expounded by Victor Pasmore, of the social benefits of art and its role in creating that healthier post-war environment for all. During a hectic decade, Heath poured his energy into not only his own art, but organising pioneering exhibitions, many hosted at his studios at 22 Fitzroy Street, and writing ‘Abstract Art, Its Origins and Meaning' in 1953. He was instrumental in pulling together his abstract painter peers into a coherent if not collective identity and he raised critical and public awareness with essays, publications, exhibitions and letters to the Spectator! That said, a distinction and certain edge was evolving between the then St Ives based abstract artists; Frost, Nicholson, Hepworth, Lanyon etc, deemed landscape or nature based abstract artists; and the London set; Heath, Pasmore, Kenneth Martin etc, who by in large categorised themselves constructivists, their abstraction a product entirely of the artist’s invention rather than, in part at least, inspired by a sensuous experience of the world around them. Heath absorbed the philosophy of John Dewey’s ‘Art as Experience’, expounding the idea that experience did not need to precede a work of art but could be something revealed in its production. Their emerging differences aside, there was a great sense of comradeship and mutual support between London and St Ives; Frost and Wynter for example taking part time residencies in Heath’s Fitzroy studios.

Heath helped orchestrate 2 ground breaking exhibitions in the mid-1950s; Nine Abstract Artists at the Redfern Gallery in 1955 and This is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel in 1956; a collaboration between artists, architects and designers; echoing the similar ambition of the Bauhaus in the inter-war years. But he was already removing himself from his constructivist peers, Pasmore and his colleagues who had rejected paint and canvas in favour of reliefs. Heath alone, within his London set, continued to paint, finding reliefs inflexible as a process, “dead through pre-planning”, and the rejection of 2-dimensional artwork, philosophically unsound.

Heath was Chairman of the Artists' International Association from 1954 to 1964. In 1957, with an inheritance from an aunt, he was able to buy 28 Charlotte Street, which he “decorated almost entirely in black, beige, and white …. Relying entirely for colour on the paintings”. (Evening Standard, April 1961). And what paintings. Heath threw himself into collecting with characteristic energy; the walls of Charlotte Street were hung with works by Courbet, Seurat, Kupka, Pasmore, Wyndham Lewis, Hilton, Peter Blake, Hockney and the larger version of Terry Frost’s seminal work, A Walk Along the Quay.

In the second half of the 1950s a new direction emerged. As the artist later described “The square or rectangular canvas was no longer the unique source of the geometrical forms that I used. I would now start independently from some other central position and the composition would spread outwards from this axis to occupy a circle or oval. I would use hessian as collage elements ..” Heath was taking a step with these more cellular, arguably organic forms, towards the inclusion of an element of nature in his work. A step that would be consolidated in the early 1960s when his work at least alluded to the human figure and sometimes landscape.

Heath exhibited 8 works in the Redfern Gallery’s famed Metavisual Tachiste Abstract: Painting in England To-day in 1957. This was followed in early 1959 by a well received solo exhibition in the exclusive Hanover Gallery where two more shows followed in 1960 and 1962. Heath’s work, influenced by his Redfern stable-mate, Nicolas de Stael, was acquiring a new boldness of brushwork and thick, richness of painted surface. The critics started to perceive in this “the demands of emotion” (The Times).

From 1956 to 1976 Heath lectured at the ground breaking Corsham based Bath Academy of Art, a liberal response to the strict structures and somewhat archaic practises of the Slade and other London schools. It sought to train exceptional art teachers and cultivate a liberal avant-garde teaching environment where free minded young artists and art teachers could develop and flourish. Frost and Lanyon where among the other modernists of the St Ives school at Corsham for some years.

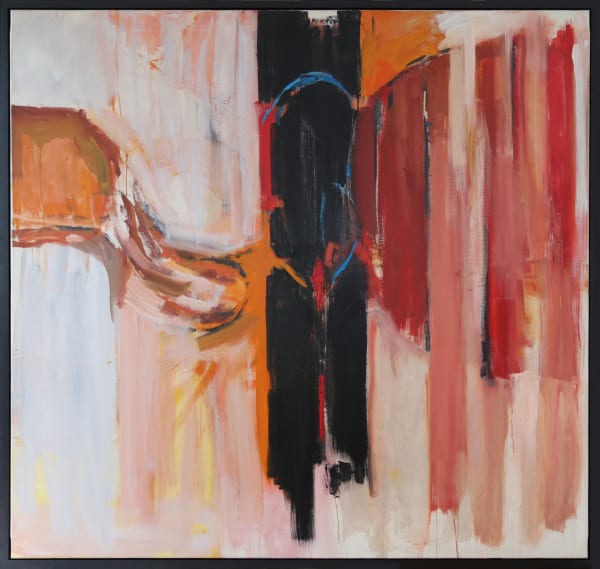

In the early 1960s a greater freedom of expression and sensuality entered Heath’s work. This was in part a product of a growing awareness of the American abstract-expressionists; in particular de Kooning and Motherwell. The size of his canvases also increased, another US influence, with the dimensions often reaching, 5, 6 or even 7 feet. Commentators, contemporary to Heath and subsequent biographers, have attributed this shift to a temporary release of the artist’s emotional self, so long consciously controlled by his process. There’s certainly a release of self-expression, aided by the bigger canvas sizes, and apparent spontaneity of brushwork although it’s known the artist, unlike his American peers, remained committed to drawing and the process of preparing numerous studies. His work however retains the fascination with movement and the collision of forms from unseen forces given expression in his works of the 1950s. But nature and the human form in particular, start to impact his work. And by 1961-64 we can discern a more explicit expression of the female form in his major works; thighs, breasts and even sexual organs appear suggested by the artist’s high energy application of paint and rounded forms. By 1963 he was further developing this oeuvre with visual juxtapositions; between hard linear and soft rounded forms, between thrusting movement and static anchored areas and between darkness and light. This produced some of his most arresting and dynamic works such as Divided: Red and Orange, 1963. Paintings of this period had simple descriptive names describing the dominant palette colours. Many years later in an interview, Heath shed some light on part of his intent in his use of figurative elements: “.. I like them to be absorbed into the movement of the whole so that a new form has been created. It’s not a particular person that you’re looking at but the feel of soft as opposed to hard forms”. The artist wished for any figurative element to be absorbed and transformed by the whole.

This was a highly successful and profitable period for Heath with these more expressionist works bought by the Tate Gallery, the Arts Council and the Contemporary Art Society as well as leading private collectors from the Mayfair showrooms of the Redfern and Hanover Galleries. In 1966 the critic and director of the Whitechapel Gallery, Bryan Robertson, in response to his latest Redfern Gallery show, described Heath as “one of the best artists in England with an intelligence, a set of values, and an accomplishment roughly comparable to Robert Motherwell’s”.

But by the end of the decade Heath sought to restore order. In the 1970s he returned to his tried and tested practise of dividing his surface up, often leaving the evidence of his process in the final work with some areas intentionally more ‘complete’ and areas of drawing left quite evident. In 1970, like Pasmore and Frost before him, Heath went to paint at the Voss School of Art in Norway, and continued to do so for 6 summers. The impact of the dramatic scenery of Scandinavia is infused into his geometric compositions in the 1970s, though sometimes still juxtaposed against softer perhaps human form inspired shapes. Throughout the decade Heath continued to show at the Redfern Gallery. In 1977 Heath was awarded Senior Fellowship of the Glamorgan Institute of Higher Education in Cardiff which lasted 3 years. This was a positive period for the artist when his abstract work was re-energised.

In his last decade of painting Heath achieves a smoother integration of soft organic forms and harder geometric forms. Movement is still very much apparent, but perhaps not the violent collisions of the earlier works. There are subtleties of palette and careful combinations of complementary colours and considered tonal contrasts. He continued to teach the next generation of aspiring artists; his generosity of spirit and desire to aid his fellow artist never waining. He died on 15 September 1992 whilst working in a French summer school, taking an after-dinner stroll with a female student. His last words to his young companion, a very English “I’m sorry”. Never one for drama or fuss.

The oft used cliché of ‘he lived a full life’ was clearly no overstatement for Adrian Heath. He survived being shot down in WW2 and captured after 4 escape attempts. He personified the wartime spirit of “kindness and pulling together”, expressed by Terry Frost. He was egalitarian about art believing that it should be equally accessible to all; and he was a man who practised what he preached dedicating years to teaching and the often thankless task of running collective bodies of artists and arranging numerous exhibitions. He certainly led a full and high octane private life. But moreover, Heath and his considerable body of work, much of it fittingly in UK public collections, played a crucial role in the development of twentieth century British art and the contribution of the visual arts to the post-war reconstruction of the country.

Rye Jane (2012), Adrian Heath, Lund Humphries

Jonathan Clark Fine Art (2007), Adrian Heath - Paintings From the Early Sixties